We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies. Learn more.

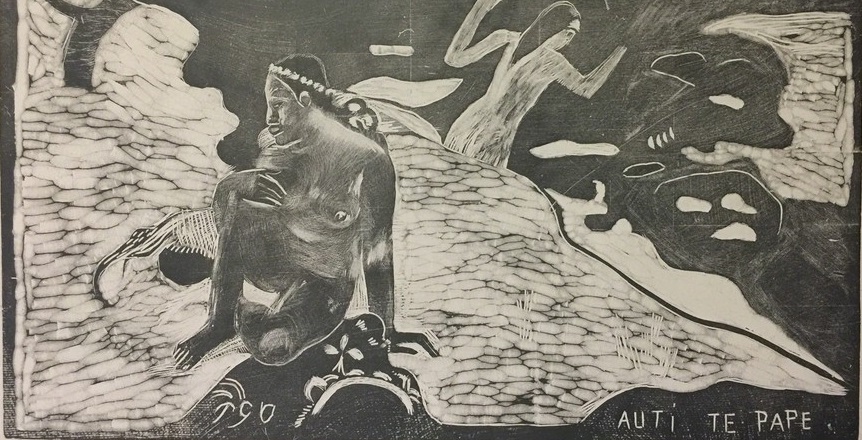

Paul Gauguin: Wood Engraver

Gauguin started studying wood- and ceramics-based arts during his first stay in Pont-Aven, Brittany, in 1886 but it was only in 1888 that he started, with Chaplet’s help, to make and sell his first complete ceramic works.

In the same year (1888), he completed 11 zincographs of subjects taken from his stays in Martinique, Pont-Aven and Arles between 1887 and 1889, and sold them during the 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris.

Gauguin produced his first wood engravings in 1894 in Pont-Aven, while recovering from a fractured leg he got in a fight with some drunken sailors over his Javanese friend, Annah. Soon afterwards, Annah went to Paris, while the painter was still in hospital, and ransacked his studio before disappearing forever.

In 1897, Gauguin sent his friend George-Daniel de Monfreid a series of small studies, adding others over the next few years. De Monfreid himself went on to become famous as a portraitist, using wood engraving as his technique.

Contrary to general opinion at the time, which held that white should be the fundamental element in wood engravings, Gauguin made dominant use of black, harking back to the naïve scenes of primitive folk art.

In 1889 the Société des peintres-graveurs (Association of painters and engravers) was founded. There was great interest in wood engraving at the time – especially after Auguste Lepère, influenced by Gustave Doré and Rémy de Gourmont, founded the review l’Imagier and in so doing launched a full-blown “xylographic movement”.

Gauguin’s wood engravings and wood blocks not only heralded the decorative approach of Jugendstil but influenced a number of major 20th Century artists such as Munch and the German expressionists in general.

Gauguin himself attributed great importance to his wood engravings, declaring prophetically: “Je suis sur que dans un temps donné mes gravures sur bois, si différentes de ce qui se fait, auront de la valeur”. (I am sure that, in time, my wood engravings, while very different from normal ones, will become valuable.)

He saw wood engraving as a return to primitive times, which was what made it interesting for him. As for the kind of wood engraving increasingly found in illustrations, he dismissed it as de plus en plus écoeurante comme la photogravure (increasingly disgusting, like photoengraving).

Gauguin printed his wood engravings himself, using neither a press nor a roller – hence their sometimes rough, unfinished look, which added to their primitive feel. Many of his blocks were then printed and signed by his artist son, Pola Gauguin, several years after his death.

Gauguin’s use of lines and his division of space create a series of contrasts that energize his works, which inspired the great wood engravers who followed him – artists like Dufy, Vlaminck e Derain.

That Gauguin’s wood blocks were intended to serve as illustrations is clear from the fact that he often set them alongside printed texts, as may be seen in writings like Noa Noa.

It represented a path towards personal freedom in an exotic realm, in a place where one may dare anything, where love can be for an unspecified period, without ties, where a man can be primitive, essential, intent only on listening to his mysterious inner voices and on pondering on the puzzle of eternity.

Discover Auti te Pape and other pieces by Paul Gauguin on our website.

Validate your login