We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies. Learn more.

Joan Miró: Painter and Engraver

“An engraving can hold the same beauty and dignity as a good painting.” Joan Miró

Born in Barcelona in 1893, Joan Miró was a Spanish painter, engraver and sculptor as well as a member of the surrealist movement.

He was undoubtedly one of the most dynamic and versatile figures on the 20th Century art scene and although he went through a number of different creative phases, what always guided him was “the instinctive force of the gesture”.

Engraving represented a significant part of Miró’s artistic production, and he always considered graphic art as a separate universe governed by its own laws, standing on an equal footing as painting or sculpture.

Joan Miró started as an engraver when he was 37 at a time when he was already an established painter with his own, highly individual, idiom.

For him, becoming an engraver meant above all dissociating engraving from the figurative dimension to which the medium has always been linked and adopting a form of graphics that used all the formal resources held in his technique. Those resources proved extremely useful in shaping the ideas that were to transform art in the 20th Century.

As with the other art forms he experimented with, his interest in engraving was total. He tried out the various existing graphic techniques from the intaglio to the drypoint, from etching to aquatint, and from woodcuts to soft ground etching, while also inventing new techniques and variations on these.

Miró’s graphic work is what best illustrates the Spanish artist’s tenacious, lifelong struggle against “facile” art.

Despite the mastery of the graphic idiom, which he perfected over the years, he never slipped into a routine but always opened up new creative horizons while at the same time searching for ever-new methods and processes allowing him to obtain faster and fresher results.

Evidencing Miró’s extraordinary fascination with the possibilities offered by engraving is a letter he wrote to the engraver Henri Goetz, who had invented the technique known as “carborundum”: “I spent a few days in Saint Paul with Dutrou, and we tried out the new technique you taught him. The results are fascinating and rather beautiful. An artist can express himself more freely and completely while also obtaining a beautiful texture and much more intense strokes. If it is no problem, I would like to use your technique." In another letter to Goetz, he wrote: “These past few days I have been working with Dutrou in Saint Paul and have become even more aware of the rich possibilities and new horizons which your technique opens up for engraving. Never before have I obtained such powerful results. I am able to express myself in a single burst of the spirit, without running into any obstacle or being paralyzed or slowed down by the kind of outdated technique that hampers one’s freedom of expression and distorts the purity and freshness of the final result”.

An interesting aspect of his relationship with graphics, and one that should not be underestimated, is the social dimension; the artist was enthusiastic about engraving because, apart from the possibilities it offered for self-expression, it allowed him to make multiple copies. Using a single plate, a number of original works could be produced, thus making art accessible to a wider audience.

Defining it “a democratic art” that was somehow more open to the world, Miró declared: “From a human and social point of view, an engraving – although a limited number of copies are printed – casts its net wider than a painting, which must always remain a one-off work that is kept religiously in a museum.”

A turning point in his studies of engraving was his return to Paris in 1948 when, while preparing for a show at the Galerie Maeght, he discovered the new medium of colour lithography at the Mourlot brothers’ workshop.This was to become his preferred technique over the following years. The illustrations in the catalogues of Miró’s lithographs published by Mourlot and present in our collection are of rare beauty.

One interesting detail is that Miró’s move from painting to prints came about as a result of his association with poets.

He produced his first four lithographs as illustrations for L’arbre des voyageurs, a collection of poems by Tristan Tzara. Poetry supplied many of the subjects found in the artist’s work, as in the case of his own poem, Le Lézard aux plumes d’or, which he illustrated in successive variations.

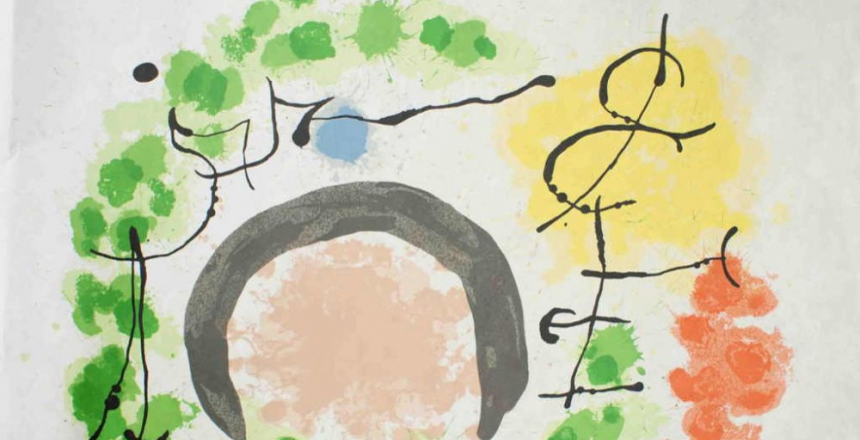

In these lithographs, first published in 1971, Miró uses solid and compact forms that serve to put across the power of his imagination. With a few brilliant, surreal elements, he brings the composition dynamically alive. “I make no difference between painting and poetry”, the artist used to say. In some cases, he would include whole fragments of poems in his works or put in words or letters that immediately became symbols, while in other instances the work’s title represented the link with the world of words. Such titles were often works of art in their own right, as in the case of Le Lézard aux plumes d’or.

Heralding Miró’s work with poetry were the illustrations he did in 1927-28 for Lise Hirst’s book, Il etait une Petite Pie, although the technique he chose was not engraving but pochoir.

This was the first time Miró produced illustrations based on the accompanying text. After a trip to Japan towards the end of the 1960s, Miró’s work underwent another change. The studies he had engaged in over the previous decades led him to open up his art to great, empty spaces, evidencing the power of strokes and “enabling his poetic idiom to rest on nothingness”.

Validate your login